The Mondragon Corporation represents a strikingly different and successful approach to our most basic economic institution, the business enterprise. The essence of this approach is expressed in its unusual ownership structure. Enterprises in the Mondragon Corporation are cooperative enterprises; that is, they are owned by the people who work in them.

Mondragon’s economic success and resilience as a group of worker-owned companies are remarkable. Mondragon firms have managed to prosper for over 50 years, the last 30 of which have been highly turbulent, including periods of severe industrial restructuring in the Basque Country as well as in the rest of the developed world.

Two of the defining features of the Mondragon cooperatives throughout their history are related to the idea of a network. The first feature concerns the idea of the network itself. Arizmendiarrieta and his followers early on saw the potential benefits of joining the cooperatives together in a group, or sets of interrelated groups, both to help each other in direct ways and to create “second-degree” network organisations to serve their common needs. The existence of this network of rims and support organisations – an embodiment of the principle of Inter-cooperation – has been fundamental to the Mondragon cooperative experience and central to its long-term success. The second defining feature has been their ability to adapt their network and organisational structures to changing needs and circumstances. Unlike other cooperative companies who operated more or less independently on a day to day basis, Mondragon’s cooperative representatives were together developing overall group policy and as the market grew larger and became more competitive starting in mid-1960s, they joined forces to collaborate in more direct ways, thus shared governance and management structures and services (mainly late 1970s-80s).

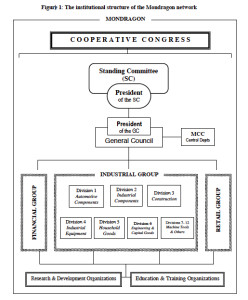

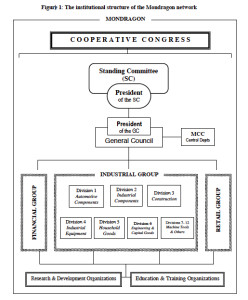

Later on, as the markets became more global and Spain was acceded to to the European Economic Community in 1986, it was realised by Mondragon’s management that the many of the old structures and policies were no longer adequate. The Mondragon Group responded to the new conditions in several ways. Two of the most important new organisation principles introduced then were: (a) partial structural unification, meaning by this the creation of central bodies with certain responsibilities and authority in both, governance and the provision of management services to the whole group; and (b) a reorganisation of member firms based on industrial sector as opposed to region (see Appendix, Figure 1). MCC was formally created in 1991, and refined in 2005-2006. It formally gathered all the Mondragon Group enterprises and support organisations under a single umbrella organisation, baptised as the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation (MCC).

The individual cooperative enterprises were distributed among the MCC’s three main business groups – financial, industrial and retail & allied – and, within the industrial group, into 12 divisions. The Mondragon Corporation as a whole and its three groups have governance and management bodies that approximately mirror those that exist at the level of the individual cooperative firm. At the level of Mondragon overall, management functions are carried out by a President and a General Council, which is comprised of the directors of the Financial Group, the Retail Group, the largest divisions of the industrial group, as well as the heads of several of the Corporation’s Central Departments (Finance, Strategic Planning and Technical Affairs, International operations, Legal and Institutional Affairs, Human Resources, innovation, New Business Development, etc). The purpose of this reorganisation was not to centralise control, but to achieve greater economies of scale, technological and business synergies, assistance and strategic planning.

The Caja remains an important institution, but now devotes itself to the banking business more strictly defined, and its development finance/venture capital functions have been transferred to several central funds in the headquarters organisation, primarily Mondragon Investments and the Mondragon Foundation, which are financed by annual investments and both pre- and post-tax contributions by member companies. The consulting and troubleshooting role of the Caja’s Business Services Division also shifted its institutional location, which is explained further below.

The central management bodies in Mondragon are accountable to two representative, democratic governance structures, the Cooperative Congress and its Standing Committee. The Congress is made up of 650 representatives and it debates and establishes basic policy which must be followed by member cooperatives. The Standing Committee (essentially an internal board of directors) consists of 21 people elected from among the previously elected boards of the sectoral groups and divisions. The Standing Committee appoints the senior management official, the President of the General Council, and must approve the president’s choices for the senior managers who sit on the General Council, that is, the group and division directors and the Directors of the Central Departments.

While the Mondragon Corporation structure may appear more similar to that of a conventional conglomerate than the former more decentralised structure did, essential cooperative principles are still in place. Each individual cooperative is, legally, an autonomous unit with democratic governance structures. Each one of them joined the MCC individually and agreed to abide by its policies through a vote of its General Assembly of worker-members (cooperativistas) and can vote to leave the MCC group at any time (as Irizar did in 2008 by a vote of 75% of its cooperativists).